Charles St by Tullochs, 1989. I loved the gutters, all tidied up now alas.

And back to London again, in 1990 and 1992 when I worked on a series of landscapes within a bicycle ride of Clapham. The second series were undertaken at the end of a long and dreary English Autumn when dusk seemed to come earlier every day.

I will indulge myself and quote from a review written by me about myself and published in the Examiner ( April 17 1983), By Margaretta Pos.

I do this self reviewing quite a lot because I think it isn't fair to expect a reviewer to get into a painters mind whether or not they like the painting; and another person's assessment isn't necessarily important to an artist, or at least it shouldn't be.

What was important was to have an idea and explore it with sincerity. The success or failure of the project often can't be measured at the time, but it is interesting to go back and look at old work and old ideas and see whether they have stood the test of time... or not

Living in isolation perforce as we have done since April of this year in Corona Time has I believe been a revelation both for me and for several artists whose work I have known well over the years.

I have watched fascinated as Edna Carolyn for instance and also Richard Klekociuk went back into the cellars of their memories and indeed their houses and retrieved a wealth of their early ideas and gave not only themselves but the world a Retrospective Exhibition of the last 30 odd years of their work.

Not only that but because they could provide exhibition dates and places they have also become their own Curators, thereby saving the world from the limtless waffle and cost of the highly paid spooks in our museums who tell us what to look at, how to look at it and worst of all its meaning.

And Nigel Lazenby has written and illustrated an astoundingly beautiful book for children....

Clapham Tube station 1990. Neon lamps in cities skew the colours into the warm range , even in the shadows where a grey pavement becomes a warm violet

But back to 1993.

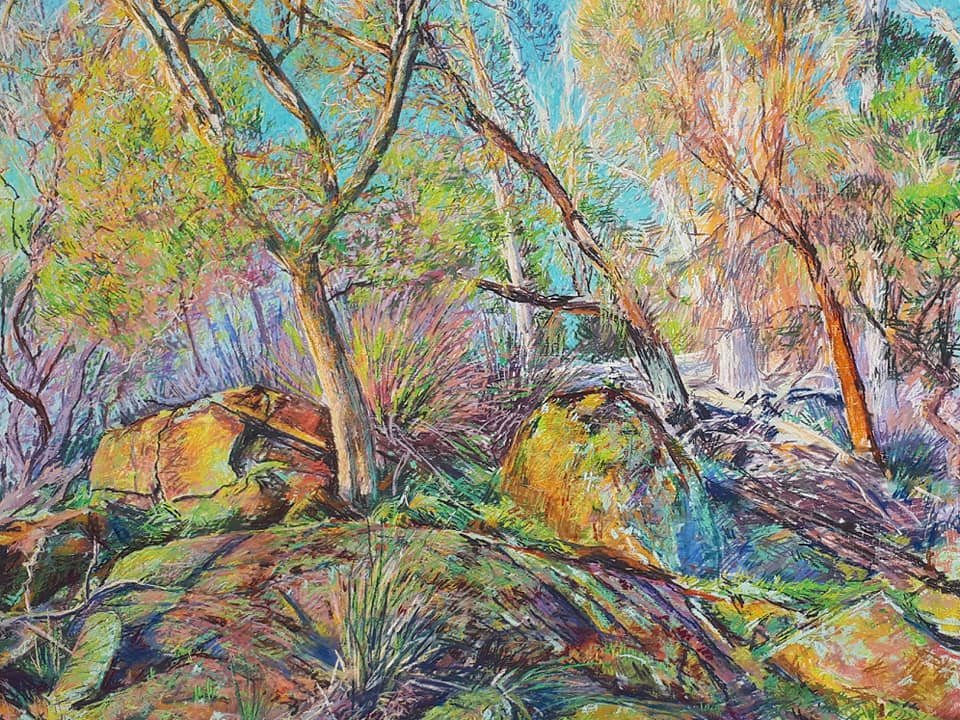

"These 20 or so paintings were a journal, a diary of my travels through Clapham Battersea, Wandsworth and along the Thames.

Half were painted by day and the other half at night with the aid of a little portable strip light hanging from my shoulder strap.( Your own light is essential at night because without it you can't tell what colours you are using. Red and green both look black under neon).

Night is just as important part of city life as day, perhaps more memorable, certainly more dramatic.

The colour is so rich; deep greens, purples and browns under the pinkish yellow of street lamps. Space becomes ambiguous and distances deceptive. People melt in and out of the shadows and the most drab corner comes alive." JB 1993

1993. By day a boring grey concrete path. At night a scene out of Dante's inferno with lost souls absorbed into their pathway and dissolving into the dark

Kirmatzis and Utting at dusk. The framers who commissioned the series can be seen at work within, Nick Kirmatzis downstairs, Mr Utting on the top floor

1990. Princess Square at dusk. One of a group of small panels Of Launceston I worked on after

the Clapham series.

1990..Beginnings of a sketch by Boags Brewery.

1990. I loved this house by The Tamar St bridge which spent the next 30 years collapsing and finally disappeared six months ago.

1990. " Night unrolls its tattered swag down Brisbane St" . Except this was a preliminary sketch of The bottom end of Charles St and Launceston was a violent lost place then with none of the dying Empire charm of Clapham Common.

1992. And in between my circuits on a bicycle round Wansdworth I could look at this Seurat in the Courtauld Galleries and appreciate the meaning of calm.